By Camilo Montoya-Galvez and Kervy Robles

JUCUAPA, El Salvador — There is a booming industry in this small town of about 20,000 residents 72 miles east of the capital, San Salvador. And it is not the sale of “jocotes,” the sour, cashew-like tropical fruit which the indigenous Pipil people honored by naming this land “river of jocotes” before the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors in the early 16th century.

It is instead, the coffin-making business.

Although jocotes remain a staple in this municipality located in the heart of the coastal Usulután province, numerous family-owned casket workshops now pepper its colorful streets as a result of the bloody gang violence plaguing this small Central American nation where Diego and Lizandro Claros Saravia now live.

As night falls in Cantón el Níspero — one of Jucuapa’s “cantones,” or rural neighborhoods in the outskirts of the town center — Diego, 23, and Lizandro, 19, prepare to rest. But sleep still proves to be difficult for the brothers. The painful memories from the summer of 2017 remain all too vivid. And for Diego, one recollection has become etched in his memory.

“They told me we were going to be deported. I asked them not to deport my brother; to only deport me; to let him continue his dream,” Diego said, recalling the time he and his younger brother were detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in the United States.

These passionate pleas by the older of the two Salvadoran brothers and Maryland high school fútbol stars were to no avail. After spending four days in a detention center, Diego and Lizandro were processed for deportation. Minutes before boarding an airplane, the two center-backs received permission to call their family and inform them of the heartbreaking outcome of their most important — and difficult — off-the-field contest.

Jonathan Claros Saravia, 30, the defensive pair’s older brother, was responsible for informing his parents and sister Fátima, 26, that the pillars of his family were on their way to El Salvador. And it was Jonathan too, who made a subsequent call to Jucuapa that left one of his mother’s sisters perplexed.

“I received the news when I was at work. Jonathan called me and told me, ‘My brothers are on a plane. Please go pick them up at the airport,’” said Beatriz Orellana, one of Diego and Lizandro’s maternal aunts. “It was a very difficult moment because we were hoping that they were going to have the opportunity to stay there.”

With little time to grapple with the unexpected news, Beatriz and her sister quickly prepared beds for the soon-to-arrive deported brothers in the family’s house, located approximately three miles away from the cream-colored San Simón Parish that overlooks Jucuapa’s bustling main public square. Soon, the humble, yet finely built cattle-raising residence — the one which José Santos Claros, 56, Diego and Lizandro’s father, financed for years and never expected to see his youngest sons return to — was beset with disillusionment.

“It has been very difficult for them — a completely drastic change. They looked sad and worried at the same time because they did not know what would become of them,” Veronica, the youngest of the Orellana sisters, stressed.

After spending nearly a decade living in suburban Maryland, the brothers felt like foreigners when they returned to their country-of-birth. “Almost nine or 10 years had passed,” Lizandro said, sitting next to his brother in a walkway surrounded by a small cattle herd and a hen house that divides the dwelling where they sleep and the one where their aunts live. “I feel like everything changed since we left.”

Although Cantón el Níspero underwent conspicuous changes while Diego and Lizandro were contesting 50-50 balls in the well-kept, green fútbol fields near Germantown, Md., El Salvador’s problems have largely remained the same. Vast economic inequality and rampant political corruption that reaches the highest echelons of government persist in Central America’s smallest country.

Over the past years, El Salvador has experienced significant industrial development, but the nation still has one of the lowest Gross Domestic Products (GPD) in Latin America, according to the International Monetary Fund. Moreover, in 2016, an alarming 38.2 percent of Salvadorans lived in households below the poverty line, according to an analysis by the World Bank.

With a government incapable of remedying these economic woes, working-class Salvadorans, like Diego and Lizandro’s family, have confronted this dire situation with low wages, scarce job opportunities and little support. “It’s just like any other poor country. There are many people who practically have no place to live — they hardly have anything to eat,” Lizandro said. “And the violence has surged because of this. Many have been practically born in poverty. And they’re tired of this. They’re tired of the government stealing so much money, while not doing anything for the people of this country.”

In the midst of this national dissatisfaction and outcry, the Salvadoran government has found itself embroiled in a series of corruption scandals during three consecutive presidential terms.

Before his death in January of 2016, Francisco Guillermo Flores Pérez, president between 1999 and 2004, was accused by El Salvador’s top prosecutors of diverting a donation of 15 million dollars from the government of Taiwan for the victims of the earthquakes that struck the Central American country in the beginning of the 21st century. His successor, Elías Antonio Saca, who led the Salvadoran government between 2004 and 2009, was arrested by the National Police in October of 2016 and is currently facing charges of money laundering for transferring more than 300 million dollars from public coffers to his political party, companies and business partners. In June of 2018, the Office of the Attorney General ordered the capture of Mauricio Funes, president between 2009 and 2014, on charges of corruption; asking Interpol to locate and extradite the former head-of-state, who has been living in exile in neighboring Nicaragua since 2016.

Like previous administrations, the current Salvadoran government which succeeded these twelve years of scandalous governance and political chaos has not managed to curb the most pressing scourges facing this Central American nation: insecurity and violence.

In 2012, President Funes’ administration negotiated a truce between the two most powerful gangs in the country, the Mara Salvatrucha, or MS-13, and Barrio 18, which, for a few months, helped reduce the alarming number of homicides in the country. However, the government-mediated truce — fragile since its implementation — was opposed by a large segment of Salvadoran society and soon began to fall apart. After taking office in 2014, President Salvador Sánchez Cerén scrapped the deal and instructed his government to adopt an aggressive stance against the warring gangs and to prosecute officials of the previous administration who devised the controversial agreement.

But these stringent measures enjoyed little success and homicide rates continued to increase exponentially. Between Diego and Lizandro’s return to El Salvador last summer and this June, 3,657 homicides were recorded by the country’s Institute of Legal Medicine. In fact, when the two former Maryland fútbol prospects set foot on Salvadoran soil, many of their compatriots were leaving the country and setting out for the U.S. because of the violence.

Despite the hardline immigration policies and rhetoric adopted by the American federal government under President Donald J. Trump and an overall decrease in unauthorized immigration to the U.S., thousands of Central American families have undertaken the perilous journey north in 2018, fleeing the rampant violence and poverty in their native countries. Apprehensions of migrant families between ports of entry along the U.S.-Mexico border has steadily increased since the summer and reached a record high in October, when 23,121 families were detained, according to U.S. government figures.

The surge led the Trump administration to implement a controversial family separation deterrence policy — which it was forced to rescind after a massive outcry — and more recently, to deploy more than 5,000 troops to the southwest border to provide logistical support to Border Patrol units. Thousands of migrants, however, continue setting up tents outside ports of entry, hoping to secure asylum in the U.S. and flee the conflict, political persecution and gender-based violence in Central America’s Northern Triangle. Cold-blooded gangs have consolidated their power in this region, comprised of Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador, through the recruitment of young men like Diego and Lizandro who lack economic opportunities.

“If they had thought differently, they might have wanted to join a gang in El Salvador. Because that’s what happens there,” said Jonathan, the eldest of the Claros Saravia siblings. “Children who do not have mothers or who are abandoned find motivation to be members of gangs.”

Despite deep concerns by their family in Germantown that they could fall into the reins of bloody transnational gangs after their abrupt and demoralizing deportation, Diego and Lizandro refused to capitulate.

“We were not going to sit back and do nothing,” Diego said. “We kept going — we continued studying and playing fútbol together.”

Diego and Lizandro’s expulsion from their home in the U.S. was a traumatizing and deeply disappointing experience. The defensive pair confessed that there was little optimism among them when they arrived in El Salvador. However, the brothers again turned to fútbol for inspiration and morale-boosting, finding much-needed solace and peace-of-mind juggling a ball in the narrow streets of Jucuapa.

Soon after returning to Cantón el Níspero, the two Salvadoran defenders tried out for several local teams like C.D. Águilas and C.D. España de San Buenaventura, looking for a gateway into El Salvador’s professional league. The brothers, however, had little success. “The first two teams did not give us opportunities to play together. And we had decided to play in a team where we were together,” Lizandro emphasized.

Diego and Lizandro believe their unfavorable outcomes in these tryouts were influenced by their lack of connections with powerbrokers in El Salvador’s fútbol sphere. These connections, or “cuello,” as they’re known colloquially in El Salvador, offer well-connected young players certain advantages over those who do not possess them. And this a predicament that many young prospects like Diego and Lizandro now face — regardless of on-the-field skills and potential.

But these are vastly different times than 1969, a year of national euphoria, when “La Selecta” qualified to its first World Cup after a lethal extra-time header by Juan Ramón “Mon” Martínez propelled the team to victory over Haiti in Kingston, Jamaica. During this time, these connections were largely useless; whoever performed better played and if you were not good enough, you had to fight. And sometimes, not on the pitch, but on the battlefield.

Earlier that year, before the national team’s historic qualification to the 1970 World Cup held in Mexico, El Salvador had been engulfed in a five-day-long, yet bloody armed conflict with neighboring Honduras — an event that renowned Polish journalist Ryszard Kapuscinski catalogued as “the fútbol war.” The conflict originated in Honduran soil, where thousands of Salvadoran immigrants were subject to persecution and violent displacement after years of escalating tensions with locals.

And the strained relations between both communities made their way into the grandstands. To keep its dream of participating in the World Cup tournament, La Selecta had to defeat its Honduran counterpart in a two-match play-off series, one which provoked violent riots and that coincided with a brief exchange of air strikes and ground attacks between both Central American countries. After days of brutal fighting, a ceasefire mediated by the Organization of American States (OAS) brought an end to the war, which killed more than 2,000 civilians, according to archives by the U.S. Library of Congress.

Despite the violence that transpired during their qualification campaign, El Salvador’s fútbol stars, including Juan Fernandez, Mauricio Manzano, José Antonio Quintanilla and “Mon,” left for Mexico in search of their humble, yet audacious World Cup dream. The squad, however, returned home earlier than expected. La Selecta lost all three of its group stage matches and was eliminated. Another World Cup participation for El Salvador would come twelve years later, with a team led by the greatest fútbol player that this land of volcanoes has seen: Jorge Alberto González Barillas, better known as “El Mágico.”

El Mágico’s remarkable career began in ANTEL, a now-defunct San Salvador-based club named after the state-owned telecommunications agency, where he amazed all of El Salvador with his superb dribbling skills and seemingly effortless ability to outsmart most defenders.

His impressive, dazzling performances helped the Salvadoran national team classify for the 1982 tournament held in Spain, where La Selecta recorded its only World Cup goal to-date at the feet of Luis Ramírez Zapata, after a masterful individual play by El Mágico which provoked indignation among Hungary’s defenders and adoration among the thousands who witnessed it at Elche CF’s Manuel Martínez Valero stadium. Despite his team’s early exit from the tournament, the quick, skinny attacking midfielder was signed by Cádiz CF, a coastal Spanish club where he immediately became a fan favorite thanks to his trademark awe-inspiring goals.

Much hearsay exists in El Salvador regarding the sudden decline of El Mágico’s career after five years donning the jersey of the Andalusian outfit. While watching their boyhood club C.D. Luis Ángel Firpo take part in a fiercely-contested home match at the Sergio Torres stadium in Usulután, the country’s fifth largest city, Diego and Lizandro listen to one of these intriguing tales about the legendary goal scorer.

A white-haired man in his 60s who was keenly observing the frenetic game while simultaneously listening to the still-developing results of other key matches that would determine the league’s playoff series on the portable radio on his shoulder told the brothers that in 1984, FC Barcelona’s manager, César Luis Menotti, keen on signing El Mágico, invited the Salvadoran star to join the Spanish giants in a pre-season tour in the U.S. The well-narrated story proceeds to a day when World Cup-winner Diego Armando Maradona allegedly set off a fire alarm at a hotel hosting the azulgranas. The entire squad evacuated, except for El Mágico, who remained in his room with a woman — which purportedly angered the leaders of the Catalan club, who decided not to sign him.

“We will never know how El Mágico would have fared in an elite team like FC Barcelona,” the loquacious man said, finishing his riveting tale.

Still impressed by the story they had just heard, Diego and Lizandro returned their attention to the second-half of C.D. Luis Ángel Firpo’s contest against Alianza F.C. The boisterous and impassioned chants from the approximately 5,000 supporters in the grandstands echoed throughout the stadium, a small venue with no team locker rooms patrolled by heavily-armed police units. It was a rousing and surreal atmosphere; one that prompted Lizandro to ponder about what could’ve been. For the rest of the match, his mind returned periodically, and with great melancholy, to the time he received a scholarship to play the sport he loves dearly — and which in that moment, he was watching from the stands. The deported center-back could not escape the painful memories of those dreams that had been suddenly derailed; physically embodied by a letter his family received after his deportation.

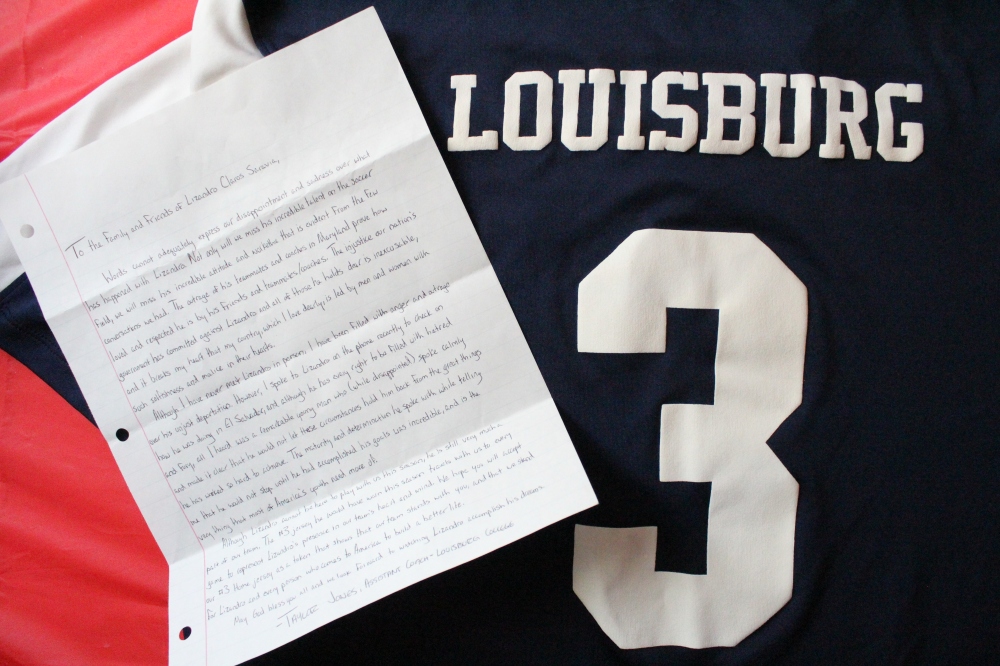

“The injustice our nation’s government has committed against Lizandro and all of those he holds dear is inexcusable, and it breaks my heart that my country, which I love dearly, is led by men and women with such selfishness and malice in their hearts,” Tyler Jones, a former assistant coach at Louisburg College, the two-year school that offered Lizandro a scholarship, wrote in the summer of 2017.

During the waning days of the summer break, before the start of the pre-season, the former Hurricanes coach was enjoying a warm afternoon with his wife in the tranquility of their home when he received a phone call. Knowing that many of the new players who lived out-of-state would call seeking advice as they moved to North Carolina, the young proponent of total fútbol initially saw nothing unusual about Lizandro calling him.

“I expected to hear Lizandro’s voice, but it was his sister’s voice, who was just sobbing uncontrollably,” Jones said, remembering how unexpectedly devastating that afternoon turned in a matter of minutes. “She just said, ‘they took them, they took them, they have my brothers, ICE detained my brothers, please help.’”

Diego and Lizandro’s rapid deportation, which Jones described as profoundly unjust and antithetical to the values of the U.S., disturbed the coach deeply, especially because there was little he could do to prevent it. Frustrated and outraged, Lizandro’s would-be coach knew he needed to find a way to express his vehement disapproval of what had transpired. Jones penned an eloquent and poignant letter praising Lizandro’s character, and sent it to the Claros Saravia family in Germantown, along with the No. 3 jersey Lizandro chose to don for the season he never played.

“I spoke to Lizandro on the phone recently to check on how he was doing in El Salvador, and although he has every right to be filled with hatred and fury, all I heard was a remarkable young man who (while disappointed) spoke calmly and made it clear that he would not let these circumstances hold him back from the great things he has worked so hard to achieve,” Jones wrote in black ink, referencing a 10-minute call with Lizandro that he vividly remembers.

Before bidding farewell, the young coach emotionally implored Lizandro to continue pursuing his dream of becoming a professional player, even in the face of great adversity.

“I have absolutely not given up. This is my dream and I am going to continue to do whatever is necessary and will continue fighting,” Lizandro responded with conviction, despite not knowing what laid ahead.

II: “God gives his toughest battles to his strongest soldiers”

Nearly 2,000 miles away from the suburban Maryland high school whose team they led to a regional title, Diego and Lizandro follow a familiar routine. The brothers wake up in the early mornings to attend classes, pursuing degrees in mechanical engineering and international business, respectively. When these English-taught classes conclude, they spiritedly make their way back to the dormitory they share. The Salvadoran center-backs have lunch, take a quick nap and pack their socks and fútbol boots for their 4:00 p.m. rendezvous on the pitch.

Although this schedule is reminiscent of the one they religiously abided by in the U.S., the brothers are not carrying it out in Maryland, or in El Salvador for that matter, but in the Republic of Nicaragua.

When they were deported in early August of 2017, Diego and Lizandro had resigned to the idea that they would probably never have another opportunity to attend a university and join a collegiate team. And their fruitless efforts to play together in El Salvador’s professional league on their return to Jucuapa exacerbated the brothers’ desperation. Their affectionate and protective sister Fátima, however, assured them that everything had happened for a reason.

“The door closed here. But many more will open up over there,” Fátima recalled telling her demoralized siblings.

And it was during this bleak and difficult moment for the brothers that an unexpected opportunity — the door that Fátima promised — arose. After hearing the brothers’ compelling story, the Latin American campus of the Florida-based Keiser University, located in San Marcos, a city in southwestern Nicaragua, offered Diego and Lizandro a scholarship to study and play fútbol at the institution.

Initially, the brothers were hesitant about moving to a foreign country, especially after such a dislocating and disheartening experience. Their family, however, urged them to accept the indispensable opportunity.

“They told us that life wasn’t over, that we had to keep going and that God gives his toughest battles to his strongest soldiers,” Lizandro said. “We had to keep going and look for better opportunities — even if they weren’t in the U.S.”

In the fall of 2017, the defensive pair moved to this Nicaraguan town of 30,000 residents named after Saint Mark the Evangelist in the Carazo Department, which lies between the Pacific Ocean and Lake Cocibolca, the largest in Central America. For decades, the highlands of this volcanic land located south of Managua, the nation’s capital, have made for ideal grounds to cultivate coffee, which has been one of Nicaragua’s chief exports since President José Santos Zelaya facilitated the country’s entrance into the global financial market in the early 20th century. And it was precisely during Zelaya’s time in office that an American lumber merchant named Albert Adlesberg introduced the region to baseball by sharing with locals the fundamentals of the sport which had become the “national pastime” in the U.S. Soon after, baseball clubs like Southern and White Rose were founded. And in 1891, the nation’s first official match was held in Managua. Since then, baseball — much like coffee — has been recognized as an integral part of Nicaragua’s national identity; something Diego and Lizandro immediately discerned when they arrived to begin their school year.

When they joined Keiser University’s fútbol team, the brothers encountered a completely different style-of-play, which they attributed to the country’s dim level of interest for the sport compared to the ardent and widespread baseball craze among Nicaraguans.

However, this is not the only reason for fútbol’s stagnation in Nicaragua.

Over the last few years, the deep-seated corruption and avarice plaguing the administrative sector of Nicaraguan fútbol has hampered the development of the sport in this Central American country, as well as the growth of its infrastructure. The National Stadium in Managua is arguably the most telling illustration.

In 2005, world fútbol’s multibillion-dollar governing body FIFA financed the construction of a national stadium in Nicaragua through its Goal Project initiative, launched in 1999 to help fútbol associations in developing countries build new training pitches, venues and offices, improve existing infrastructure, subsidize administrative expenses and support youth academies.

After receiving its first $400,000 grant in 2001 to establish a national youth training center, the Nicaraguan Fútbol Federation received a total of $814,105 in FIFA funds to construct the National Stadium through a second Goal Project grant in 2005 and a third one in 2007.

In 2011, the former powerful FIFA president Sepp Blatter, who would later be dogged by corruption allegations, presided over a ribbon-cutting ceremony inaugurating the stadium. But, years later, the venue still resembles an unfinished construction project.

The late former president of the country’s federation, Julio Rocha, hired several engineers who had masterminded the construction of the Estadio Victoria in Aguascalientes, Mexico, to reproduce their success in Nicaragua. But in 2018, the National Stadium bears little resemblance to the 25,000-capacity home of Club Necaxa.

In May of 2015, Rocha, who led the Nicaraguan Fútbol Federation for 26 years, was arrested by Swiss authorities in a hotel in Zurich along with six other FIFA officials following a sweeping transnational corruption probe by the U.S. Department of Justice into world fútbol’s ruling body. The following year, the high-ranking Nicaraguan sports executive pleaded guilty to accepting bribes in exchange for granting marketing rights to the national team’s qualifying matches for the 2010, 2014, 2018 and 2022 World Cups.

Apart from this administrative malpractice, Nicaraguan fútbol has recently confronted another problem. The deadly political turmoil that erupted across the country in April of this year prompted officials to cancel the CONCACAF Women’s U17 Championship only four days into the tournament and to suspend the international friendly match between Nicaragua and Argentina on the eve of the 2018 World Cup in Russia.

Earlier this year, a nationwide uprising began to brew as the massive anti-government protests in la Vieja Managua, the capital’s colonial neighborhood, failed to dissipate. Although they were 14 miles away from the epicenter of this escalating unrest during their second school semester, Diego and Lizandro began to fear the ramifications of the unfolding strife.

The government of President Daniel Ortega, a former guerrilla leader, found itself facing widespread public opposition after it proposed tax hikes and cuts to several welfare programs. Large manifestations quickly swept the entire nation, especially on university campuses — which, for many decades, had been bastions of support for Ortega’s leftist party.

The so-called “Trees of Life,” metallic monuments in the heart of Managua and totems of Ortega’s grip on power, were toppled by angry protestors during the third week of April — the same week Diego and Lizandro decided to return to El Salvador, a country they had left because of the same violence that today has plunged Nicaragua deep into a sociopolitical crisis.

“They had to come back. They were desperate and frightened. They didn’t even know where to buy food because everything was closed due to what was happening in Nicaragua,” Beatriz, one of the brothers’ aunts, said.

III: “There’s no American dream unless I’m in the United States”

Taking advantage of a quiet and serene afternoon in Cantón El Níspero, Diego and Lizandro work on their remaining coursework for the spring semester, which the university allowed them to finish online. Sitting side-by-side on the dinner table, the brothers use their computers to complete their assignments and to monitor the worsening violence in Nicaragua.

Since the uprising began in April, President Ortega’s administration — along with pro-government paramilitary units — has carried out a bloody crackdown against dissident groups in the country. In the course of four months, the unrest has killed more than 300 people, sparking scathing criticism of Ortega’s handling of the crisis by the international community, including the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights.

When Diego and Lizandro received the opportunity to study at an American university in Nicaragua, their family was eager to have the brothers move to a country that seemed much safer than El Salvador.

Today, however, the situation has changed drastically. Diego and Lizandro’s mother, Lucía Saravia; their father José; and their siblings, Fátima and Jonathan, fear that the youngest members of their family will continue to study in a country still engulfed in political chaos.

While Diego and Lizandro await a peaceful resolution to the turmoil in Nicaragua as their fall semester concludes, their family members in Maryland face their own concerns due to changes in U.S. immigration enforcement and policy under a Trump administration steered by immigration hawks.

Because of the White House’s termination of the Temporary Protected Status (TPS) program for El Salvador, Diego and Lizandro’s father and approximately 200,000 other Salvadorans living in the U.S. will lose their work authorizations in the fall of 2019. José, like his fellow TPS holders, will be left with two options: leave the U.S. or remain in the country illegally.

Like her father, Fátima also faces much uncertainty regarding her immigration status. Under the presidency of Barack Obama, Diego and Lizandro’s sister obtained a driver’s license and a work permit through the executive order that Obama enacted to create the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program to shield so-called DREAMers, young undocumented immigrants who came to the U.S. as children, from deportation.

In September of 2017, Fátima was participating in a pro-immigrant rally outside the White House to condemn her brothers’ deportation, which had occurred a few weeks before, when she received more spirit-breaking news: U.S. Attorney General and notorious immigration hardliner Jeff Sessions announced the government’s decision to wind down and end DACA.

“When they said ‘DACA is finished,’ it was a very big shock for me because I realized I wasn’t just fighting for my brothers now, but for myself as well,” Fátima said.

Jonathan, like Diego and Lizandro, did not qualify for DACA as he did not meet the requirement of coming to the U.S. before the age of 16. He was 17 when he set foot on American soil.

Because she came to the U.S. in 2004, Lucía did not qualify for TPS like her husband. She is undocumented.

More than a year has elapsed since Diego and Lizandro’s deportation and their chances of returning to America anytime soon remain scarce. “I don’t want to close the door, but I think it’s very difficult, in my assessment, for them to come back in the near term,” the brothers’ former attorney Nick Katz indicated. “I’m hopeful that one day they can come back. But I don’t see a viable path immediately to that happening.”

Despite the legal limbo that has bedeviled the Claros Saravia family, they continue working long and exacting hours, hoping that their efforts will one day lead to a much-awaited reunification. Their tireless advocacy and relentless work ethic — prime illustrations of the extraordinary toil performed by immigrants in America despite great adversity — has even been recognized by members of Maryland’s congressional delegation.

Former Democratic Congressman and 2020 presidential contender John Delaney, who represented the district where the Claros Saravia family lives, said that if immigration reform is passed on Capitol Hill, “there’s potentially a way for [the brothers] to come back.”

Sen. Chris Van Hollen (D-Md.) sent the brothers a direct message. “America is your home. We want you home. And we’re going to do everything in our power to bring you home,” he said.

Diego and Lizandro’s absence is ubiquitous in the Claros Saravia family’s new home in Gaithersburg, about a 15-minute drive away from their former townhouse in nearby Germantown. Portraits of the brothers adorn the walls of the second-story apartment and a collection of their trophies from on-the-field triumphs have been neatly lined up in one of the rooms.

Every night, Lucía lights a set of candles. The practice has become instrumental in preserving the family’s constantly-tested faith; the same one José relied on when jumping off the bus that was rolling down a steep ravine in southern Mexico; the same one that motivated Lucía to cross the arid desert with bloodied and scratched knees; the same one that equipped Jonathan with the strength to tell his family that Diego and Lizandro were on an airplane back to El Salvador; and finally, the same one that empowered Fátima to mount a fierce campaign of activism to denounce her brothers’ deportation.

Encouraged by this admirable faith and unwavering support, Diego and Lizandro continue chasing their dreams thousands of miles away from the fútbol fields of suburban Maryland.

“We don’t know if we will return to the United States. But if we get the chance, we still want to graduate and look for work,” Diego said, before being interrupted by his more stoic brother. “If it’s not in Nicaragua, maybe in the United States. The key is to graduate, find work and support our family,” Lizandro said. “And if God permits, to help our parents so we can be together again.”

Despite his commitment to continuing his studies and playing fútbol in these foreign fields, Lizandro is well-aware of the 10-year ban that he and his brother face from entering the U.S., the country he still regards as his home.

“Maybe our dreams didn’t end, but I like to be realistic and think about where I am,” he said. “And there’s no American dream unless I’m in the United States.”

___

Note by the editors: Our two-part series Dreams Derailed chronicles the deportation of two young Salvadoran brothers and fútbol prospects — as well as their lives after being forced to abandon their home in suburban Maryland and return to violence-plagued El Salvador. Read part one here.